Has Photography Crossed a Line?

Is photography, now, more of a technology than it is a form of art?

I call myself a photographer, and have been one, professionally, for over sixteen years. I’ve witnessed the rapid decline of film, the exceptional growth of digital, the rebirth of film, and everything else in between. I started a petition and led a fight to keep Fuji pack film in production (to no avail), I was a beta tester and pioneer with Impossible Project (now Polaroid), and have purchased, tested, used, and sold dozens of different camera models and brands. Throughout this time, I’ve learned that photographers are some of the most insufferable people—often relying on gear, technical specifications, and camera value to inflate their brand, as well as their ego. They create circles, cliques, of popularity and they are perpetually trying to eclipse and out perform members of their own community in order to better serve their needs. They will befriend you over commonalities and culture only to voluntarily “stab you in the back,” shortly thereafter, in a filthy effort to benefit themselves. [Insert. “but not all photographers” comment here]. And yet, some of my greatest friends, and moments in my life, are due solely to the medium.

Everybody is a photographer now and, truthfully, that’s not embellishing too much, if at all. Phone cameras are of phenomenal quality, and everyone with a smart phone has the capability of photographing with technology that photographers from most of the twentieth century couldn’t, possibly, fathom. The camera is only the beginning—there are thousands, if not millions, of filters, presets, software programs, hardware, and now A.I. programs to “help you become a better photographer,” when in reality they accomplish the opposite. In today’s world, you can easily call yourself a photographer the moment you open a camera, or phone, box and make your first photograph. No testing, no schooling, no license required. The current technology makes your photograph relatively perfect, instantly. And on a more impactful note, you’re able to showcase it to a very large portion of the world within seconds.

Photography has always coexisted with technology, but it is now more of a technology product than it is an art form.

Before you “lose your mind” and attempt to destroy me in the comment section, as I’m sure some of you may be eagerly awaiting to do, I urge you to take a deep breathe and some time to think about what I’m stating. First and foremost, I am not suggesting that there are no “artistic photographers” or photography cannot be art. They are out there, I know them, I admire them, I am inspired by them. I consider myself one. However, as a whole, photographers have become so absurdly addicted to camera specifications and mindless, dull, buttons and gadgets, that the camera companies themselves, including historic brands like Leica, constantly regurgitate needless and cumbersome “bells and whistles” to attract a crowd. The bizarre part is that people eat it up like the last cupcake on the table at a wedding reception.

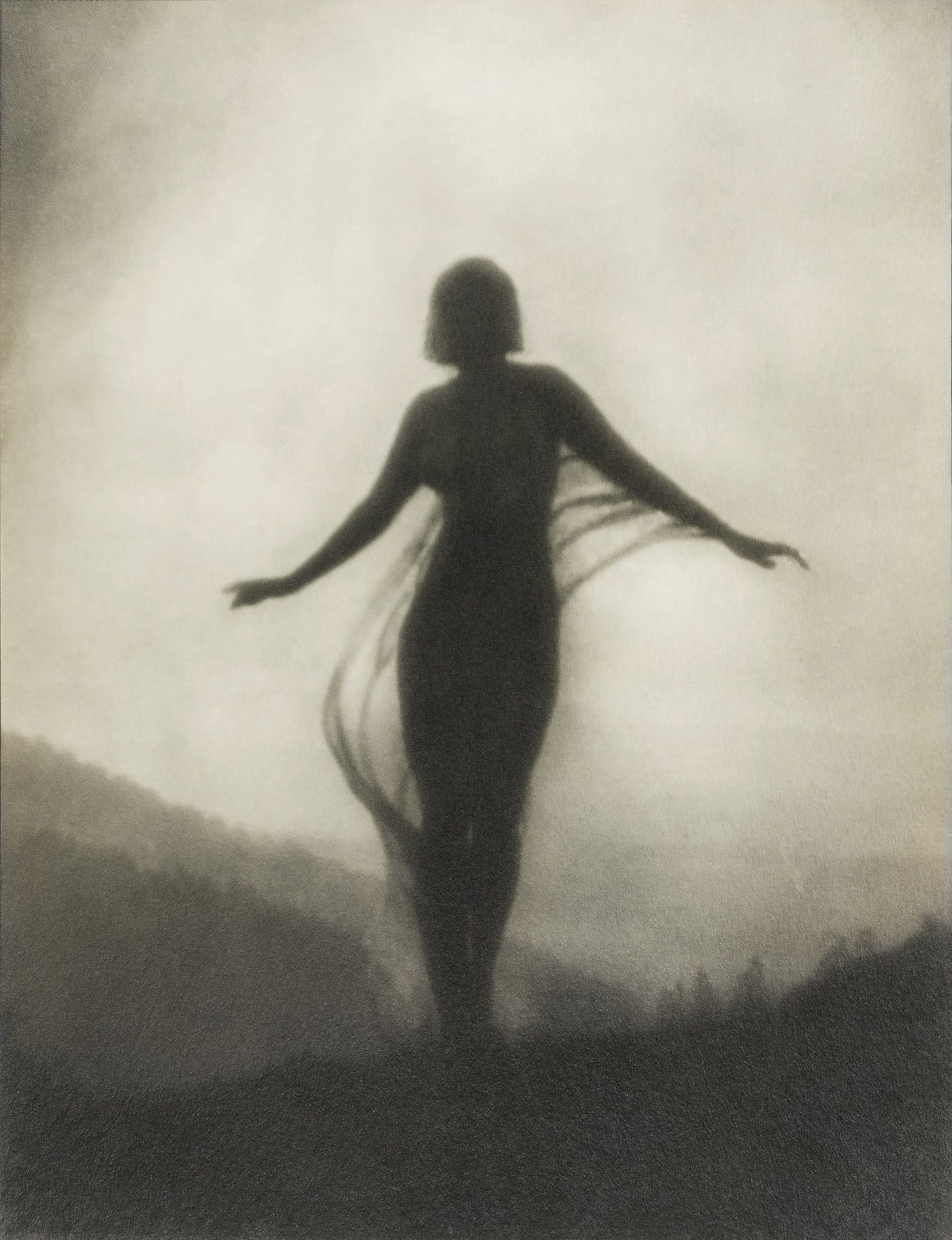

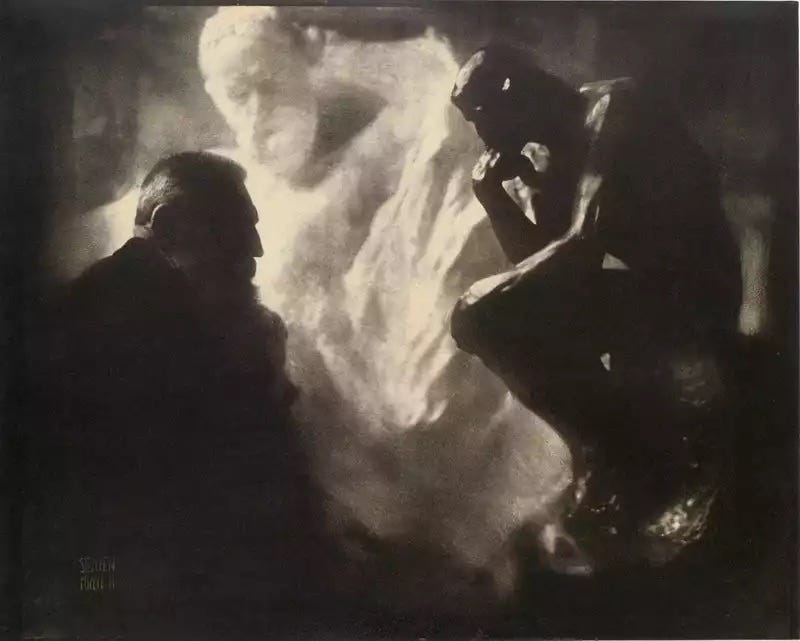

Was photography ever an art form? I believe it was, still is, and still can be. At the turn of, and into, the twentieth century we had the pictorialist and surrealist movements which featured photographers such as Anne Brigman, Alfred Steigletz, Edward Steichen, Man Ray, Gertrude Kasebier, Edward Weston, and many more. Anne Brigman was denied entry to a photography competition because she edited the photograph to make it more “artistic.” She also made people aware of how ridiculous that was, and was quoted as saying that she had every right to utilize all tools at her disposal, to make any photograph she wanted. Conceptually, I do agree with her, at least to an extent. One could argue that Man Ray popularized the artistic style of photography (he also considered himself a painter, not a photographer), and even Salvador Dali utilized a camera in some cases. The world was waking up to photography as an artistic expression, and not just pure documentation or portraiture. However, to become a photographer you had to invest a considerable amount of time, and money, to learn the craft. The cameras available were basic in their core function, but challenging to use.

The polar opposite is happening in society today. Cameras are readily available, relatively affordable (yes, some are expensive, but most are not), and, with built in features and settings, they’re ready to use right out of the box. At this moment, you more than likely have hundreds, if not thousands, of photographs in a folder on your mobile phone. In the early twentieth century, it could take years to make a thousand photographs. Today, some photographers capture five thousand images in a single one-hour session. We live in an era of social media, video streaming, online groups, and endless platforms for sharing. You can connect your camera to your phone via bluetooth and upload images directly to the cloud within seconds. Imagine explaining this to a photographer a century ago! The pictorialists are rolling over in their graves, I assure you—not because the technology exists, but because so many photographers rely on it almost entirely, even celebrating its dominance. I would argue that a large portion of those we call “photographers” today would never have been considered such a century ago.

Why write any of this? Who cares what camera or software someone prefers? Why should I care if someone is more obsessed with gear than with quality? Because photography altered the trajectory of my life and it reshaped who I am as a human. My concern is not with any particular style or individual, but with the technology itself. Without questioning, there is no progress. Without progress, stagnation sets in. And so, has photography crossed a line? Yes, I believe it has. In it’s current state, modern photography has more in common with a tech company than with an art form.

Consider oil painting. While artistic styles have shifted across centuries, the process and tools behind the medium remain largely consistent. Brushes, paints, and canvases have certainly improved, but when you buy a brush, there is no need to download new software to make it function. You do not have a laundry list of technical specifications in order to help make a decision about which brush to purchase, or need to sync it with your computer over bluetooth. The medium still relies, primarily, on human talent. Can the same be said of photography today? My answer is no.

This is an excellent example of why I turned to film, and older cameras as a budding photographer. I crave simplicity, but simplicity with intent. I am weary of technology invading and overcomplicating life. Cars, coffee makers, refrigerators, even washing machines—everywhere, convenience often becomes obstruction. Technology, of course, has its place, especially in medicine, but in photography, I find it mundane and cumbersome. And just like ChatGPT has, already, affected how people think, cameras, and their technology, are already doing the same for photographers. Not long ago, photographers used to say, “get it right in camera.” Now, more often than not, I hear, “fix it in post.” I fear this shift is here to stay—and while it may not affect me directly, as we each have the choice to use the medium as we see fit, it will undoubtedly prey on anyone new to the medium, and discourage the use cognition, observation, and intellect in the act of creation.

Do you find yourself feeling similar? Have I bothered or frustrated you? I’d love to hear your thoughts, even if you aren’t a photographer. A lot of what was written can be applied to many artistic forms.

As someone who very unprofessionally messes around with photography, I think I didn’t actually engage the art form methods at all until I just recently ditched my nice point and shoot and switched to using a set of manual prime lenses exclusively. ( And much to the point of this post, who cares what the new camera is behind them.) The limitation of the lenses has made me gain a living feeling of aperture and focus and of the wild glass behavior itself, and a level of intent that’s now required even just by selecting a focal length before stepping into the view.

It’s pretty expensive to go this route, but I feel connected to it now and excited by it too because my decisions are making unique captures that nobody else could ever have.

My phone camera feels like a data entry tool for documenting 2D moments, even more so now with this change.

Your painting comparison is worth considering, but not for the reason you stated.

Painting is closest to the photogram in photography, not to anything we might refer to as a photograph. The photogram is meant to fix light and shadow to some substrate, much as painting does with chroma and shade, through a single degree of technology.

Painting uses pigment carried in a medium applied to a surface; photograms use ferrous oxide or silver halide or platinum salts coated on a surface. At this level, each is basically a single degree of technology used to accomplish the task. Certainly, there is a very long and rich history to the variations in the artistry of pigments in oil, water, or petroleum products that comprise painting, a history that is awe-inspiring and jaw dropping.

The photogram has a much less richly developed history because of its limitations with verisimilitude and spatial renderings and the challenges of controlling tones in a single exposure. While photograms might likely admit of very complex spatial depictions, it seems few artists have pushed them so far. Instead, photograms are more often considered the poor cousins of photographs.

In order to move beyond the limits of the photogram, one has to add degrees of technology, often many degrees, to get the effects people want to secure for a “photograph.” These layered technologies - lenses, focus, aperture, shutters, films, printing papers, etc.- are fundamental to our ideas of photography, whether they came with the box cameras of Edward Weston, requiring time, patience, and experience in the narrow conditions for exposure to master, or they bedevil the modern DSLR and smartphone with their overboard control of multiple technologies.

Photography is so steeped in technology at every level that it has always raised questions about its relationship to art. Sometimes the questions have been about the reduced presence of the human hand, and at others they have been about the sheer proliferation of cameras and images. Sometimes they are how the technology is disrupted, used, or abused.

Indeed, photography cannot be separated from its technology; it falls completely apart. In almost every era in photography, photographers have bemoaned additional technical layers and waxed about a simpler past.

So dispense with the angst and simply make your determination about the value of any piece of art by looking at it and asking yourself if it moves you. Let all the hype and incessant chatter (and your own thoughts) about the latest and the best and all that crap . . . disappear. Decide if the print you just made moves you; whatever technology you used to get you there was necessary to that work in time.

My brother wants the latest in autofocus for bird photography; I couldn’t care less about autofocus. Give me a sharp lens and the ability to fully manipulate the field and depth of focus.

We each make the images we want. In the final prints lie the only real qualities that matter for our different intended purposes. All else is noise.

And comprehending what, in your work, constitutes art is, well, a lifetime’s work.