“When I work, I’m very practical, like a butcher who knows exactly where to put the knife, and I leave the poetry to others.” — Nicola Samori

Nicola Samori is a recluse. At least to some degree. He’s considered a “blue chip” artist and yet you’ve, presumptively, never heard of him. I only stumbled upon his work, accidentally, several years ago. As cliche as it may sound, good things enter your life when they are least expected. If enter his name into Wikipedia and for the most part, you won’t find too much.

He does an excellent job of remaining under the radar all the while producing incredible artworks. He is showcased in, generally, one show per year. His website shows almost nothing and hasn’t been updated in over two years. Interviews are hard to come by as well, with only a handful out there, and many just being opinion pieces with a line or two from the artist.

An excerpt from an opinion piece written in the Village Voice—

“Samori bases much of his work on Renaissance imagery and brings classical aplomb to his figures. But having been born in 1977, he is separated from that world by the revolutions and revelations of modernism. The camera took away the necessity for painting to represent human beings and their events, and soon thereafter abstract art liberated raw color and form from any narrative demands. Yet no less a paragon of abstraction than Willem de Kooning declared, “Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented,” because painters know that their medium, lithe and organic, can never be completely divorced from the meat of existence.”

In an age where living artists tend to rely on social media to be seen, and in some cases, thrive, it’s quite astonishing to find a fairly young (45) artist taking almost no advantage of this potential spotlight. Social media has become, unfortunately, a starting out point— a means of gaining traction and attention. Whether we like it or not it can transform careers and provide a vital platform for artists to be recognized. While I envy the days of it not being around, it has changed the art industry. Just like musicians and bands can become widely recognized without having a record label backing them, gone are the days where artists relied solely on being represented by a gallery. Like Samori himself, I can remember a time without having to partake in social media so I can understand the allure of staying away.

From an interview with Contemporary Art Issue in 2020—

Interviewer:

And without forgetting that la pittura è cosa mortale (painting is a mortal thing). Is this to say that you distance yourself from the idea of the timelessness of art, or better, from its illusory eternity in favor of a vision of the work’s inescapable degeneration, as of all things that remain?

Samori

I’ve always had an ambiguous relationship with art defined as a viaticum of immortality. On the one hand, I’m seduced by its capacity to challenge our biology, while on the other, I’m annoyed by the privilege that we’ve granted it. Perhaps that’s why I accelerate the process of degeneration of the images: I transform them into something fragile like a dry leaf or like the wings of a butterfly, something that you have to take care of so it doesn’t crumble before your eyes.

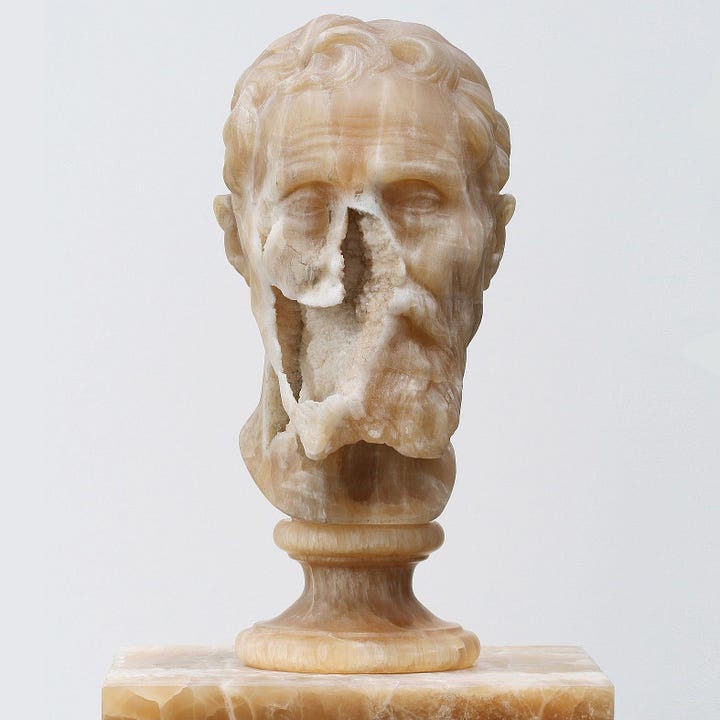

Samori’s ability to shift between two mediums, yet retain the nuances and beauty of each, is both exceptional and mesmerizing. Paintings often mimic sculptures, and sculptures mimic paintings. There are plenty of artists that stick to one medium, and there are many others that don’t. In a personal note; I shift between photography and painting— there are times where the photograph doesn’t portray exactly what I had in mind. For me though, it’s more of a dabble. For Samori, it’s a necessity to convey the idea appropriately.

“Painting and sculpture have lived side-by-side for a long time in my studio and so end up imitating each other: the painting detaches from the support and protrudes forward while the sculpture nourishes itself from the earthy polychromy that encrusts the natural cavities of the rock.” — Nicola Samori

More from an interview with Contemporary Art Issue in 2020—

Interviewer

What are your thoughts about the dark side in your work, and what role does melancholy play?

Samori

Darkness is the condition of things, whereas light is only a temporary episode and one that expires. It’s not a coincidence that miracles and visions were always represented by a ray of light at some point in the painting. Wherever you see more light in an old painting, you can bet that there’s a miracle in the air.

In the past few years I’ve seen a resurgence of baroque artwork, and this more “moody” approach has slowly developed a cult following. Classically trained painters are more inspired by the renaissance style of old masters like Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and Vermeer. Photographers such as Francesca Woodman and Anne Brigman have received international attention and acclaim. This new crop of painters are gaining traction and it’s a welcome sight (I’ll be focusing on a few of them in future reads). When photography became “mainstream,” painters began to renounce the portrait style and flocked to the abstract style, divulging their feelings on canvas using color, geometry, force, and subtlety. While portrait painting never disappeared, it definitely has not been the highlight of the most of the 20th, and 21st century (so far). I truly believe we are on the verge of another renaissance in the art world— harkening back to the “old days” with painters giving a fresh take on a more traditional style. Nicola Samori is only the beginning.